-

- Kablooe Design

- Blaine, MN

Other articles by Kablooe Design

DESIGN DRIVEN DEVELOPMENT: THE D3 PROCESS

It may be easy to envision a computer or a coffee house making an emotional connection with a user, but oftentimes developers and engineers have a hard time believing the need for that connection holds true when the product is something more

- Author: Thomas E. KraMer

- Published: Wednesday, July 11, 2012

- Keywords: design, process, strategy, innovation, industrial design, product design, product development, prototype, mechanical engineering, innovation, development, design managementdesign, process, strategy, innovation, industrial design, product design, product development, prototype, mechanical engineering, innovation, development, design management

DESIGN DRIVEN DEVELOPMENT: THE D3 PROCESS

Thomas E. KraMer

Kablooe Design

9162 Davenport St. NE, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55449 USA

763-785-9595, 763-785-9446 fax, ideas@kablooe.com

In today’s world of product development there are many things to consider when trying to successfully take a product to market, the least of which is not the development process itself. Although there are many process theories, books and literature discussing the process, and a swell of information about product development and project management, so much new product development ends up unsuccessful. According to the Kellogg School of Global Marketing at Northwestern University, over 80% of new product development efforts fail [1]. Robert Pirsig, author of “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” recognized this fact when he stated, “There is so much talk about the system, and so little understanding.”[2]

The purpose of this investigation into the development process is to create a much more successful process methodology, and the objective for doing so is threefold. The first part is to create an understanding of the role that design plays in the overall product development process, and to ask the question; “what is design?”, and “what are we trying to accomplish with it?” The second is to ask “why?”, and to understand why there is such an important role given to the design discipline and its defined development process steps for successful innovation and deployment. The final objective is to understand what a more detailed, functional and successful product development process model looks and feels like.

WHAT design is: The first question product developers must ask themselves when embarking on a product development journey, regardless of whether you are an individual entrepreneur or Proctor and Gamble, is “what am I trying to do here?”, or what am I trying to create or sell?” it does not matter what your particular product is, the initial answer is always the same; you are creating and selling an experience… a user experience. Successful product companies know this, and have capitalized on it for their success. Apple Computer aired a now famous commercial during the super bowl in 1984 for the first Macintosh computer. (Figure 1) This commercial spot has gone down in history as one of the top ten most effective television commercials of all time, and an Apple computer never appeared in the commercial at any point. Yet somehow everyone knew what the spot was for, and it was hugely successful. The makers were very skilled in creating an experience that was comprised of emotion, perception, and the promise of satisfaction. Good design thinking maintains that this is always exactly what is being done when a product is being developed. This is evident in the experiences that Apple computer users talk about compared to other personal computers, and the perception they have of themselves as being in a group that uses this product, as well as about how they are perceived by others. It is also evident in the satisfaction they feel not only with the actual computing tasks, but with how they identify with, and are associated with that product.

Another good example is Caribou Coffee. Caribou has changed a $.50 cup of coffee into a $5.00 experience in relaxation and comfort. The feeling of a cozy cabin with a fireplace roaring and your feet up on a cozy north woods sofa is what a user is getting for their five bucks. (Figure 2) Both of these companies created an experience for their customers in the products they developed, and they did it intentionally and purposefully. They used three of the major elements of experience which we will briefly explore for the purposes of understanding the role that the practice of design plays in the overall development process; emotion, perception, and satisfaction.

In order to be successful, a product must make an ‘emotional connection’ with a user, according to Mark Dziersk, Vice President of Industrial Design at Brandimage/laga and adjunct professor at Northwestern University Kellogg [3]. This is a connection that we cannot plan for or detect with traditional engineering methods of development. Researchers know that 95% of humans mental processing is done on a subconscious level [4]. This means we must use more ‘humanlike’ methods to gain an understanding of how a product will interact with a user on that emotional level. With this level of subconscious processing activity in continual motion it is apparent that ALL products connect with users emotionally in some way. Unfortunately, if it is not planned, it is far more likely that the emotional connection to the user will be a negative emotion rather than a positive one.

It may be easy to envision a computer or a coffee house making an emotional connection with a user, but oftentimes developers and engineers have a hard time believing the need for that connection holds true when the product is something more technical, such as a medical device. With medical devices, the end user is not a typical consumer. The end user may be a physician, a nurse, a technician or a patient. The actual customer or buyer might be a hospital purchasing person, or hospital director, physician or patient. When designing for a physician, engineers and developers may think that function stands alone as the only design criteria. However, the effect of an emotional connection can never be underestimated. Recently the design team at Herbst Lazar-Bell designed a line of tools for orthopedic surgery. These tools (Figure 3) have had a positive impact on the sales of tools for the customer, Smith&Nephew, and have generated positive feedback from the surgical community. In this study we will attempt see how the use of ‘design thinking’ throughout the process leads to the success of products such as these.

A large part of a product user’s emotional connection to a product comes from perception. Human perception is an astonishing thing; however, according to visual equity analyst and principal of Applied Iconology, Inc. J. Duncan Berry, the human mind only has the ability to process 40 bps of information, yet 10,000,000 bps of visual information are thrown at it from the surrounding environment. [5] This means that people tend to only notice the things that are important to them, or things that are meaningfully different. In experiments conducted in the UK, participants did not even notice that the experimenter was exchanged with another person when they were focused on a left brain activity such as looking at a map or reading a sheet of instructions. This phenomenon is called “Change Blindness” and is seen when a person is occupied with a mental activity. To the product designer this means that we need to focus on what it is that we want a user to perceive and devote their mental attention to. This also means that the most important aspects of a product must be clear, brand recognition should be sensed, and the semantic cues of the function obvious.

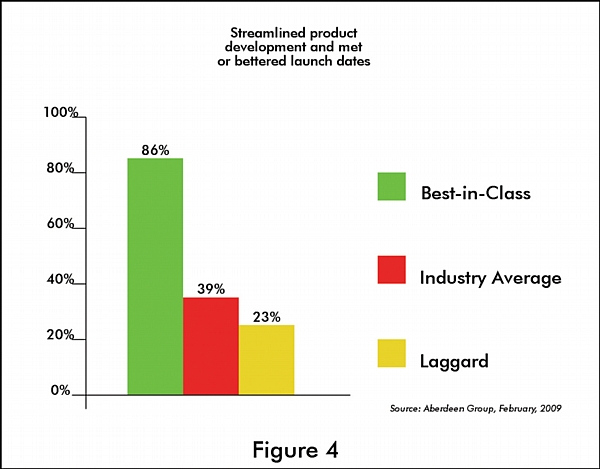

The final part of the experience and the emotional connection is delivering on the promise that the product speaks. The product must be authentic in its aims and claims, and it must provide the satisfaction that the user expects when it is used. It must visually and semantically speak the language of the promise that it claims to deliver, and then deliver it. Style alone will only go so far, and if there is no substance behind the style users will quickly discredit the product, which will eventually kill the brand. Beauty and brains, form and function must work together to visually deliver the emotional experience that is intended for the user. When this occurs, and satisfaction is delivered, product success is possible. (Figure 4)

As a detailed, holistic, and effective development process system was being developed in this study, it became apparent that the need to define the design discipline and describe how it fit into the process was necessary. The first step in doing this is defining what design and design thinking really is.

“Design Thinking” is a popular buzz word and is a term used to describe a mental process that uses the practices of design disciplines throughout the development process. “Design Mindfulness” is another term used to describe the idea in a similar way. For purposes of clarity, we will use the term ‘Design‘ in this paper to infer and encompass the idea of ‘Design Thinking’ and ‘Design Mindfulness’ as well as the practices and disciplines of good design methodologies.

The first step in understanding the role that Design must play in the development process is to define what Design is not. The most common misconception of Design is what we call the “pigeon hole" effect. The pigeon hole effect occurs in a variety of ways. One of the most common is when a product manufacturing company hires a designer or creates a design department, and then only assigns to them the task of taking what engineering has already made and trying to make it look nicer. This is most common when a company adds just a designer or two to its staff in an effort to make the company more “design minded”. Usually companies that create an entire design department have a strong vision for the role of Design, which led them to the development of that department in the first place. When designers are tasked merely with making things look better, they are in fact being pigeon-holed as artists, and left with an extremely small part of the entire design process in which to work, and this part is usually undertaken too late in the process to contribute in other ways, which perpetuates their pigeon holed position as they continue to work only in that capacity. In reality, nothing could be farther from the truth. It is true that a designer must be an artist, but that is only one of many hats that designers wear if they are true industrial designers and operating with design mindfulness.

A second way the “pigeon hole effect” is seen is when companies outsource to design firms, and just bring the design firm in to enhance the look of a new product that engineering has already developed. This shows that the manufacturing company’s thinking is that the designer is merely a stylist to be used at the end of the process, and they miss the value that Design brings to the other phases of the process.

Design is not just creating curvy shapes on objects, or trying to apply last minute ‘sex appeal’ to a product. It is not selecting a color, and a shape or style that a customer might like, and it is not just applying ergonomic principles. These things are a part of the role that design plays, but are certainly not the whole of the role that design actually needs to play in the process.

What design is, according to Walter Herbst, principle of design firm Herbst Lazar-Bell in Chicago, is “The ability to use a problem solving process, and distill the potential solution ideas into practice”. [6] It encompasses innovation, which is another buzz word used frequently today. True innovation, according to Larry Schmitt, founder and president of Inovo Technologies, is “The ability to search out and discover new product opportunities, turn them into useful products that are successfully adopted by users, and create a profitable business for the company”. [7] Without user adoption and company profit, the product is just another good idea that went nowhere. Design inherently uses a process that accomplishes these things, and it imbibes the ideas of experience, emotion and perception into its product development thinking to create a very holistic process, which we will explore in more detail later. Achieving the proper flow and ultimate effect of the process usually requires some outsourcing, as the company may not have the necessary resources to complete the process, or it may face an uphill battle against management or departments to bring in a new process. At times, an outside consultant may have more success introducing a new process as an experiment within a company before the company commits to a change of process. In Warren Haug’s “Management and Metrics for Product Development” he links sustained business growth with effective innovation, and he develops the links that show how effective innovation demands new technologies, and new technologies can be developed jointly with effective strategic alliances, which will yield a competitive advantage. [8] Design is the embracing of a process of development that can create these kinds of alliances, and within that process it places activities into a proper order, including various kinds of research, human factors studies, ergonomic investigation and application, marketing, prototyping, engineering and production activities. At times this idea that Design and innovation must use a structured process can seem like counterintuitive procedures that are impossible to coexist together, but according to Peter Erickson and the innovation department at General Mills, true innovation actually occurs best inside of a balanced process. [9]

WHY design is so important: The next question is to ask why… specifically, why is Design so important in the overall product development process? There are several reasons, and one of the most important is that when used effectively, Design can prevent some of the major pitfalls that failed product development efforts encounter. One of the worst pitfalls is for a company to actually have no documented development process whatsoever. Studies have shown that companies that adopt a standard, methodical development process (best in class) far exceed the success rates of their counterparts. (Figure 5) More commonly is for companies to be missing portions of the development process. Later, when we explore the details of an effective process we will see how product companies commonly miss important portions of the process. Oftentimes company process charts will show some initial research, and then expect prototypes for customer evaluation and market studies to appear. The creative ideation work that actually needs to occur between those two points is left as a “miracle” that needs to somehow occur. This occlusion is due to the general unfamiliararity that many project managers have with some of the more creative “black box” portions of the process. Oftentimes research is lacking or missing altogether as well, and this tends to lead to a product being launched that nobody really wants to buy.

Another common pitfall when Design is lacking in the process is to undergo parts of the development process in the wrong order. If the process is started without proper research, or with bad research, then inevitably more research is done later in the project at an inopportune time, which causes all of the steps which should be done after research to be done over again. Oftentimes, a company will start with a concept and become married to it before research is done. This leads to an unfortunate ‘movie critic’ syndrome, where after production is finished research data can be gathered, but it is too late to do anything about it other than criticize it. If engineering is started too early in the process much time and effort can go into the creation of CAD files and final solutions before the best direction is chosen. Then when research and design factors lead to a different direction, valuable time and resources have already been expended. Arthur Frye, inventor of the Post It Note states “Good product development takes time, and a culture built around Design and innovation”. [10] A sufficient amount of time must be spent on the appropriate design activities BEFORE significant engineering time is spent on a project. Dziersk describes this condition in terms of consumer experience. He claims that the old model for development was to start with an existing brand and an idea for advertising a new concept for that brand. Then an idea was created to be used, and a lot of money was thrown at the concept to develop it. It would be engineered into a single, working product, and then some “industrial design” styling was thrown at it, and it went out to the market, where a consumer experience, either positive or negative was created. [3] Design calls for a new model of the development process. In many ways this new model is the inverse of the old. In the new model, the consumer experience is considered first. Sufficient research and design effort goes into defining what the user experience needs to be, and only then does development activity occur, which will define the functional and aesthetic elements of the product. If one subscribes to the old model of the process this may seem counter-intuitive, but in all actuality companies must plan Design into their process system long term in order to innovate quickly and intelligently, providing a smart product that users truly want. Studies by The Aberdeen Group [11] have shown that companies that using this kind of methodology are 62% more likely than their competitors to develop products that meet or exceed revenue targets. (Figure 6) The discipline of Design is a very holistic one, which makes it extremely important in the overall development process. Some universities have been working for decades to try to bring a design degree program to their college, but the segmentation of the college into divisions or ‘silo’s’ has rendered the task as nearly impossible, as there is no design department at many state colleges. Without a department and a budget, no one can decide on where Design would fit, or how it will be funded. This is not uncommon, as Design is really a discipline that works across the silos of academia and industry. The true Design discipline contains elements of research, marketing, engineering, advertising, legal, humanities, art, and social sciences. Consequently, Design cannot be pigeon-holed into any one given ‘silo’. It is this very nature of Design however, that gives it extreme value in the process. If an analogy had to be made between Design and another profession, one would say that a good design manager is much like Beethoven, being both a composer and an orchestra conductor, first writing and planning the symphony, then bringing various people with individual and different skills and roles together to make one unified effort. Every development project needs a champion to be in charge of moving the project forward to a successful completion, and given the description of the Design process one can see that a design manager would be a correct fit for the leader of the development effort and the champion of the project. The fact that this way of doing things is so commonly rejected in today’s manufacturing environment however is evidence that it is precisely what is needed given the 80% failure rate of new product development efforts. Richard Lueptow, professor at the McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science asserts that there is a “dance of two questions” when embarking on a product development journey. [12] The two questions are “what is possible?” and “what is needed?”Lueptow asserts that scientists, theoreticians and experimentalists will tend to start their work by asking the question “what is possible?” Engineers, he claims, will start their work by asking “what is needed?” (Figure 7) What is really essential however is what product designers have been trained to do. Product designers tend to ‘dance’ between need and possibility, and it is this harmony that is exactly what’s needed to lead a cross functional team through the development process.

Unfortunately, this methodology is very seldom adopted in the US today. Part of the reason is the"comfortability factor". It is just too easy and too comfortable to keep on doing things the way they have always been done. If engineering has always provided the project management, then it is much easier to keep it that way than it is to try to institute a process change, and of course, the bigger the company, the harder it is to change. The paradox is that as humans, we are wired to notice things that are different, and there must be some internal appreciation applied to that difference because of the recognition of it. Yet when people are asked to do something differently, they tend to resist the change because of the uncertainty or effort that goes with it. It is this conflict which tends to create ‘silos’ of disciplines in academia and industry. We see this when people are labeled left brainers or right brainers, and they tend to specialize themselves and their activities in that one direction. What makes a designer unique however is that they do not fit into either one of these categories, but rather into both. A good designer uses both halves of the brain proficiently, and possesses skills of the engineer/scientist, and of the artist. Leonardo DaVinci is the perfect example of what a true designer is. DaVinci was proficient in the arts, as well as science, engineering and philosophy. This makes for a very well rounded person, which makes designers and the Design discipline such a good candidate for leading the development process. Oftentimes when people are labeled ‘right brained’ or ‘left brained’, they forget that the two halves of our brains are not severed, and we have the ability to use both. The designer strives for a harmonious balance between the two. This balance is not always easy to achieve, but it is necessary in Design, and therefore must be a personality trait in any good designer. It is a balance between the expressive and the controlled; the artistic and the scientific; the chaotic and the process oriented, the sacred and the profane. If any successful product is inspected, you will find a balance in that product, even if it doesn’t initially appear to be so. Even if the product looks overly rugged, or extremely sleek, it has in its very nature a balance that brought it to its place of success. The very fact that it is successful testifies to this. The Macintosh ibook laptop may appear to be a very simple, smooth, modern work of art and sculpture (Figure 8), yet it has highly technical components inside that balance its beauty with functionality. If it were not so, it would only be art, and not a product. A beautiful jar or vase may have a superb aesthetic quality, yet it possesses the functional ability to carry water or hold flowers.

It is this dual-sided balance and the holistic nature of Design with its unique process steps that make the discipline of Design so important to the product development process.

HOW a good process works: The next step is to understand how a more full, detailed and balanced product development process looks and works. We started by investigating the current status quo of product development process in the industry, then we developed a similar process controlled by Design, with Design elements infused throughout. In 2007 the Institute for Health Technology Studies, in cooperation with researchers at Stanford University conducted a study to determine the most standard or common development process among medical device manufacturers in the US. [13] The processes that these companies generally followed were condensed into a process chart shown in below. (Figure 9) We can see that all functional groups are listed on the left of the chart (with the exception of Design), and phases are spread across the x axis. It could be argued that Design is really part of the Research and Development functional group, but upon review of the tasks listed in the body of the chart for R&D, we see very few design items there. This may not be surprising when considering the propensity for new product development effort failures. This seems to indicate a relationship showing that a portion of these failures may be due in part to the lack of the Design discipline in the currently used processes. Upon inspection we discovered that there are many gaps and missing parts to the current process, the most obvious of which is the complete absence of a Design department. The fact that Design is ‘tucked in’ under R&D shows that companies are not using Design as the coherent, cross disciplinary force that leads and drives projects through the development process. In most cases product companies are using Design in a more ‘strike force’ like fashion to do small tasks here and there throughout the process. This leads to Design becoming an afterthought in the project, rather than the driving force in part because nobody really knows who is responsible to foster and drive Design into all of the functional groups and phases of the project. We also see that research and ideation are completely missing from the process, yet prototypes still appear and are evaluated. The dangers of this have extreme ramifications as this means that more than likely the product will have to be designed over and over again several times, consuming large amounts of time and money, and innovation may be completely lacking if the proper creative steps are not engaged to create those prototypes. We also see that evaluation steps and other development steps are out of order, which will also cause redundancy in the process. The formulation, concept and feasibility phase is really too large, and encompasses too many activities in a mixed up order. This phase needed to be separated into several other phases, which we will see when we examine the improved process. Secondary design steps are also missing or hidden within engineering, which makes them occur too late in the process. According to Phil Corse, marketing professor at the Kellogg School of management, one of the major contributing factors to the failure rate is that research is not conducted, it’s not conducted effectively, and it is not implemented. [1] Developing a product without doing extensive and proper research is a lot like throwing darts at a dartboard, and hoping that you will hit the bull’s-eye, however, very few product companies have aim that is precise enough to accomplish success in this fashion, especially when the target is moving. Herbst asserts that development efforts will fail ‘every time’ without ethnographic research and deep immersion into the user space.

With careful consideration to Design and its methodologies, revisions have been made to the process chart to create an improved product development process (Figure 10). As you will see, this process chart includes many of the previously missing components to the process.

First of all, in order to visualize Design’s involvement across discipline silos and throughout the process, the most directly involved areas of Design are shown in green. You can see that Design is involved in all 7 of the stage gates, and is directly involved with activities in 5 of the functional groups, as well as indirectly involved in the other five. You can see that this makes the Design Discipline the logical choice to lead the project and provide the project champion as leader guide. Unfortunately, this is rarely the case in business today. Most product companies do not have a holistic view of Design or its’ practices, and therefore miss out on the opportunity to use it throughout the process and as a driver to keep the process on track. A good design team or independent designer will possess the necessary skills and talents to drive this holistic process.

Next you will see that the first phase between gates one and two has been broken into two phases: Research and Ideation respectively. Research requires activity from 6 of the 10 functional groups, with a possible 7th being manufacturing. The phase between gates 2 and three in the existing process has also been broken into two phases; the Design and Mechanical Development phases. With the addition of these elements, the new process now consists of seven phases and six ‘phase gates’, where ‘go’ or ‘no go’ decisions are made regarding moving to the next phase. The increased number of phases decreases the amount of risk involved. Much like any gambling endeavor, as the risk goes down, the spending and investment can go up, which allows more time and resources to be spent on a project as it progresses, and the ‘go or no go’ phase gates allow this to happen.

As it is now defined in this new model, there are seven phases to the development process, of which Evaluation is the first. Evaluation is the time when some of the ‘due diligence’ is done to see if the problem and possible product solutions are viable ones in terms of technical feasibility, costs and return on investment, timeframes, resources, market trends, customer base, marketing avenues, clinical requirements and reimbursement strategies.

At the Evaluation phase of the process a product concept should not exist. There should be an understanding of the product opportunity, and rough ideas of how to fulfill that opportunity can exist, but no specific product concept should be conceived at this time. From a preliminary understanding of the opportunity the management team conducts a financial review looking at costs of goods sold, market tolerance for item costs in the category, capital investments, manufacturing costs, and potential returns. Design will be involved by assisting the creation of projections of costs for development, prototyping and production.

At the same time the marketing department is analyzing the market in terms of competitive space and trying to find those ‘white areas’ where this opportunity may lead to a product idea that has a novel attraction to the users and strong intellectual property potential. Determinations need to be made by marketing about the nature of this particular market, if the competition is too strong to compete effectively, and if the market is the correct size for an eventual return on the investment. Design will assist Marketing in all of these steps by discovering competitive units and evaluating the strength of their product designs and creating opportunity maps, value proposition options, positioning strategy charts, gap analysis, and design language maps.

During Evaluation the Research and Development department will be doing an early risk assessment. This will be done by the Design Team, and will attempt to identify risks to the success of the product project in many areas including technical feasibility, timeframe feasibility, user safety, compliance, and threats from users, competitors, market environment and physical environment. This assessment will help guide the core team in weighing the pro’s and con’s for advancement of the project.

At the same time, the legal department will do a preliminary search of the current intellectual property landscape for the area, looking for clutter as well as open opportunities. Legal will try to develop a very preliminary opinion on whether or not there is room to be playing in the space. Design is involved in this process by reviewing the findings and investigating the most closely matched findings to offer opinions concerning the ability for new products to be developed in the space.

At this point Regulatory and Reimbursement must check to see if they feel there is room to play in the space by confirming that reimbursement codes exist that the potential product will fit into, and a clear regulatory path seems appropriate. Design may assist in these activities by offering potential characteristics of potential concepts to see if they would fit into the strategy, and inversely, examining the strategy to help form potential fitting solutions later.

This Evaluation phase, along with the Research phase, is often referred to as “the fuzzy front end”, as there is no defined product at this point. Notice however, that even though a product does not exist yet, the involvement of the Design discipline is very deep. This makes a project leader from the Design discipline the perfect candidate to be the leader of the cross-functional management team, and the champion of the project, as Design is integral to every step in the phase.

In the Research phase we have activity from the same 6 functional groups. At this point the cross functional management team will create the team list of all the required personnel on the project, planning for resources from all ten functional groups. Also at this time the team will also put together a preliminary project plan and timeframe which will include important milestones. General information from all functional groups is gathered to put this plan together.

In this Research phase, the legal, engineering and marketing teams will work hand in hand to support the Design team in a 9-fold research path. These nine steps are patent searching, developing a competitive landscape, ethnographic research, human factors investigation, demographic studies, early requirements formulation, limitation evaluation, criteria list development, and a go or no go decision.

The patent search in this research phase continues to go deeper into the preliminary work that was done in the evaluation phase. The goal here is to look for patens on similar or otherwise related products that could spurn door development ideas, as well as patented ideas that may already provide product solutions for the space. In this step an opinion will be developed as to whether the best route is to design around existing patents, license current ideas, or change directions.

Design will investigate existing and upcoming products to provide a competitive landscape. This will illustrate the potential difficulty of the competition and reveal where the opportunity gaps lie.

User research helps to understand who the potential users are, and what their needs might be. This work is best done by the Design team with the help of marketing. Included in this endeavor is ethnographic research, which analyzes users in their native environments; interviews of users and other key people; self experience with the designers in a real setting; Q & A sessions and surveys for key stakeholders and users; focus groups; and blogs and other online industry and academic forums.

The Design team will also research human factors data to develop relevant constraints to the potential product through the investigation of human interactive elements and physical human needs. This data helps to provide a logical framework within which new ideas can evolve.

In the research phase, the marketing department will also put together a demographic profile of the users in the product opportunity space. This data will break down groups of people into subgroups according to their components. The Design team will then correlate important demographic data with potential design requirements. This data, along with all information gained from all of the research steps mentioned above, will be the framework to create a preliminary list of technical and design requirements. These requirements are then turned into a preliminary specification list with the collaboration of cross functional management, marketing, engineering, regulatory and Design. At the same time this group will also discuss and list limitations to the product or product opportunity. These limitations should include restrictions imposed by the client, manufacturing constraints, regulatory and reimbursement issues, and potential user and market acceptance hurdles.

At the end of the Research Phase, the Design Group will put together a comprehensive criteria list that condenses all of the information learned from the research and from the requirements, specifications and limitations list into tangible product criteria which will be used to guide the development process effort. This criteria list will require the acceptance with signatures of the entire cross functional management team, as well as any other key stakeholders within the customer’s organization. It will then be used to help customize the strategic design plan for the rest of the process.

The second stage-gate exists after the criteria list is accepted, requiring a ‘go’ or ‘no go’ decision of the cross functional management team. Details of the requirements for a ‘go’ decision can be seen in Table 1.

Gate 2 Go or No Go Decision Factors: |

|

Is the value proposition viable and sustainable? | Are the product risks acceptable?

|

Could a preliminary list of design inputs be formed at this point? | Is there a confirmed criteria list that is accepted and signed off by all key stakeholders? |

Table 1

As seen in the development chart, the development process continues after the Research phase through an additional 5 phases and four gates with similar ‘go or ‘no go’ decisions for that phase. These are ideation, concept development, mechanical development, production assistance, and support. The Design Team works through a nine step ideation process in the ideation phase and then conducts an internal concept review. Other activities occur during this phase involving the legal, regulatory, reimbursement and manufacturing groups as well. In the concept development phase the Design Team works through a seven step process and conducts user evaluations of mock ups, and creates a preliminary risk analysis. Legal and manufacturing groups continue to have activity in this phase as well, and it is during these two phases that iterations of the product concept need to occur. The creative and innovative nature of these phases makes them a prime time for revisions to occur and for new paths to be investigated. The evaluation and research phases, if they were done correctly, should have provided enough information about the product and the users that changes in criteria should be minimal and incremental, and certainly not surprising. If these kinds of revisions and criteria changes occur in the mechanical development phase the cost of revising the concepts or criteria will usually strain the budget beyond allowable parameters. If concept iterations are occurring before the ideation and design phases the company runs the risk of adhering to a product concept too early, and narrowing the scope of innovative possibilities. This is why well crafted evaluation and research phases are so important, as they allow the ideation and design phases to be as iterative as necessary, which in turn allows the mechanical development phase to be more focused and intentional.

There is a large amount of activity in the mechanical development phase from eight of the ten functional groups. During this time the Design group is working with marketing to get a customer or user evaluation of early prototypes. The Design and Engineering groups are also working together to go through a ten step mechanical development process, create prototypes, and complete a verification and validation assessment as well as a design failure mode and effects analysis.

Phase six is the production phase, and it also has activity from every functional group as the product is in the process of being ready to be launched. It starts with the design team going through a seven step pre-production process, updating and reviewing the DFMEA, verifying design inputs with design output, and finishing the design history file. The product is then sent to manufacturing and all departments prepare for ramp up and delivery of the product.

The final phase is product support which includes data collection, and potential revisions and improvements, and concepts for next generation products by the design and engineering groups. At this phase the product begins to have a life of its own, and the process can begin again with new product generation based on data collected from this products market performance and user acceptance.

This overall process reflects the holistic intent of the Design discipline, and of Design in general. It incorporates what we earlier defines as design thinking throughout the process from beginning to end, capturing its important benefits including investigation, discovery, and innovation that only good, thorough Design can bring. It finds opportunity gaps, incorporates user needs and desires through experience and emotion, provides for well informed innovation practices, and optimizes functional and mechanical development efforts. It prevents unnecessary redundancies, improves end goal clarification, and makes an effort to bring many functional groups together in a unified, orchestrated fashion. When implemented strategically for each product effort, this process can be like a beautifully orchestrated symphony, and can yield amazing and beneficial product results.

References

[1] P. Corse, “Marketing Principles for New Product Developers”, Kellogg School of Global Marketing, Chicago, April 2009.

[2] Pirsig, R. M. 1974. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. William Morrow & Company, New York. 373pp.

[3] M. Dziersk, “Essentials of Industrial Design”, Northwestern University Master of Product Development Program, Chicago, April 2009.

[4] Zaltman, G. 2003. How Customers Think: Essential Insights into the Mind of the Market. Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston. 356pp.

[5] J.D. Berry, “Consumer Semiotics; Mapping the Experience of Value for New Product Development”, McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science, Chicago, April 2009.

[6] W.B. Herbst, “Introduction to Product Development”, Master of Product Development Executive Program, Chicago, April 2009.

[7] L. Schmitt, “Innovation Processes and Tools”, Design of Medical Devices Conference, Minneapolis, April 2009.

[8] W.R. Haug, “The Management and Metrics of Product Development” Northwestern University, Chicago, April 2009.

[9] P. Erickson, “Innovating on Innovation” Front End of Innovation Conference, Boston, May 2009.

[10] A. Fry, “Post It Notes Were Not an Accident” Design of Medical Devices Conference, Minneapolis, April 2009.

[11] Rowell, Amy, February 2009, “The Top Five Principles for Successful Product Development,” Research Report, Aberdeen Group, Boston, MA.

[12] R. M. Lueptow, “Gap Analysis in the Design Process” Northwestern University Master of Product Development Program, Chicago, April 2009.

[13] Linehan, J., Ph.D., and Pate-Cornell, E. M.D., and Yock, P., M.D., and Pietzsch, J., Ph.D., 2007, “A Study and Model of the Device Development Process,” Technical Report, the Institute for Health Technology Studies, Washington, DC.